by Dennis J. Maika

The first direct shipment of enslaved Africans arrived in New Amsterdam in 1655. The voyage of the White Horse came in the wake of significant changes in the Dutch Atlantic. In this blog, American historian Dennis Maika outlines how family and business connections shaped the development of a slave-trading center in Manhattan.

New Amsterdam’s residents would have immediately noticed something different about the arrival of the Witte Paert (White Horse) in the early summer of 1655. The stench of human excrement and illness emanating from the newly arrived “scheepgen,” (small ship) left little doubt that a slaver had arrived after a long voyage. A vessel devoted exclusively to the slave trade had not been seen before in Manhattan because in the past only small numbers of captives arrived irregularly aboard privateers and were sold as “prizes.” The Dutch West India Company had thus far never sent enslaved Africans to New Netherland, in spite of their hints and unfulfilled promises. The arrival of the first vessel to sail from West Central Africa was unique in another way: it was organized and funded not by the West India Company but exclusively by Dutch private investors.

Trafficking Humans

Today we wonder how businessmen—commercial entrepreneurs—could make a decision to traffic in human beings, but we must recognize that long ago, “commodifying” human beings was an underlying assumption in Atlantic World commerce. The slave trade between Africa and the Western Hemisphere was introduced by the Spanish and Portuguese in the early sixteenth century, and by the mid seventeenth century free individuals in the Dutch Republic, Western Africa, New Amsterdam and the Chesapeake easily and automatically placed financial value on enslaved Africans. As we focus on how and why such individual decisions were made by investors in New Netherland, we can see the factors that shaped slavery as it first developed in North America.

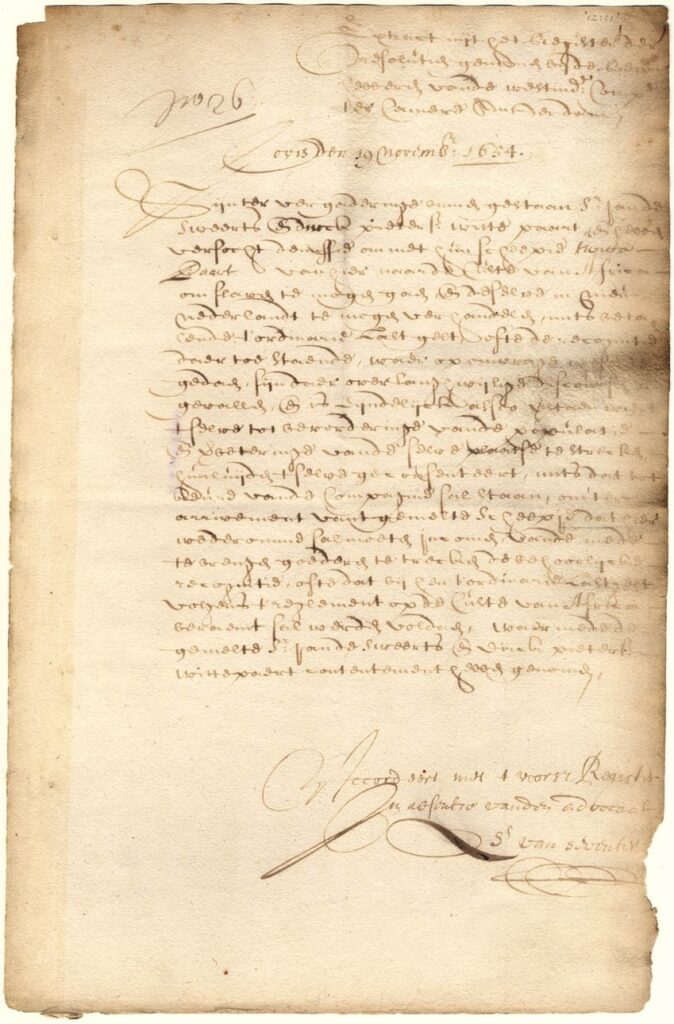

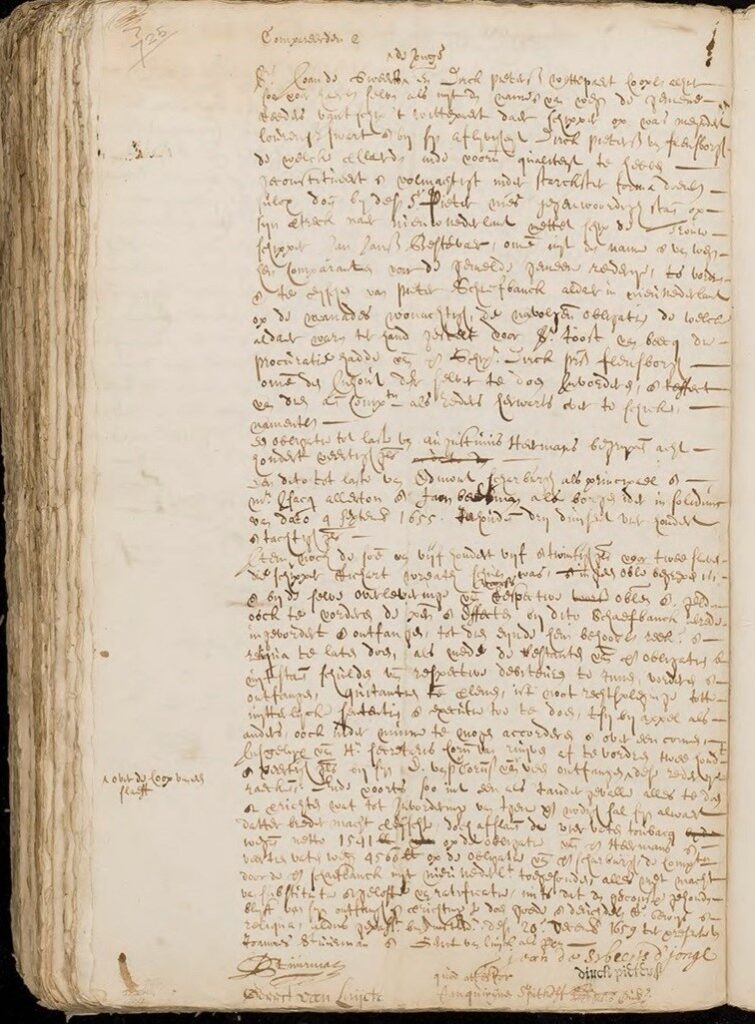

Dirck Pietersen was among dozens of seventeenth-century Amsterdam merchants willing to add human trafficking to their commercial portfolios after the West India Company’s Amsterdam Chamber opened the slave trade to private investors in the late 1640s. In November 1654, in partnership with Jan de Sweerts, he requested permission from the WIC’s Amsterdam Chamber to bring enslaved Africans directly to New Netherland. But such a venture was particularly risky—the historical uncertainty of New Amsterdam’s slave market and the many hazards and captive fatalities that would accompany an exceptionally long voyage made any profit highly speculative. Why then did these two partners decide to do what had never been tried before?

At this particular moment in time, several important developments in the Atlantic world improved the partners’ chances for success. First, the final surrender of Dutch Brazil in early 1654 not only disrupted the sugar trade but also the lucrative West African slave trade that supported it. Jan De Sweerts and his brothers Jacob and Paulus had recently left Brazil, returning to Amsterdam where they hoped to reconfigure their family’s business. Actively involved in the Brazil-West African trade, De Sweerts saw an opportunity to divert African captives previously intended for the sugar plantations of Pernambuco or Paramaribo to the West Indies and New Netherland. He hired Meijndert Lourensz Swart, a seasoned skipper with experience navigating and trading in the Gulf of Guinea, to secure a cargo of West African captives and take them to New Amsterdam for sale. That New Amsterdam could now be considered a viable slave market was due to the end of the First Anglo-Dutch War, which occurred only months after Brazil’s fall. With significant commercial growth in the years before the war, New Amsterdam had begun to emerge as a regional and international entrepot due, in part, to the exchange of Dutch imports for Chesapeake tobacco. With personal experience and contacts in that market, Dirck Pietersen knew that Virginia and Maryland planters were eager to reinvigorate their trade through New Amsterdam. He was also well aware that Chesapeake planters had become more keenly interested in acquiring enslaved labor.

It is obvious from the Witte Paert’s voyage that calculating profit based on commodifying human beings was the driving force behind the early slave trade. Any calculation of risk by men like Dirck Pietersen, and Jan de Sweerts could not have been made without assigning monetary value to human life. It is also clear that personal networks were essential in building reliable markets and exchanges. But we also learn that the slave trade, even if privately funded, could count on institutional support from Company officials and local magistrates to facilitate sales and protect investment.

The Witte Paert’s example demonstrated to those considering future slave trading that a dependable supply of captives and an expanding network of purchasers were essential components for financial success. Within five years, subsequent attempts by the West India Company depended on Curacao as a slave depot from which to bring the captives to New Amsterdam, whose position as a regional hub now added the South (Delaware) River colony of New Amstel to its network. The culminating effort of this new strategy was in the Company-sponsored 1664 voyage of the Gideon, that would travel from Amsterdam, to West Africa, to Curacao, then finally to New Amsterdam with 291 enslaved captives. Although the English invasion fleet that arrived at the same time as the Gideon temporarily altered the slaving trajectory, New York would ultimately become a slave-trading center in the eighteenth century.

Special thanks to Jaap Jacobs (University of St Andrews), Mark Ponte (Stadsarchief Amsterdam), and Wim Klooster (Clark University) for sharing many of the new discoveries mentioned in this blog.

Dennis J. Maika (PhD New York University, 1995) is Senior Historian at the New Netherland Institute.

This blog is the sixth of a monthly series with stories from the rich history shared by the American and the Dutch people. Authors from both countries will present various stories of their own choosing, from a wide variety of perspectives, in order to provide the full picture of the triumphs and heartbreaks, delights and disappointments that took place throughout hundreds of years of shared history. Not all stories will be ‘feel-good history’, however. While the relations between the Dutch and the Americans have for the most part been stable and peaceful, their shared history contains some darker moments as well. Acknowledging that errors have been made in the past does not take away from the friendship but, rather, deepens it.