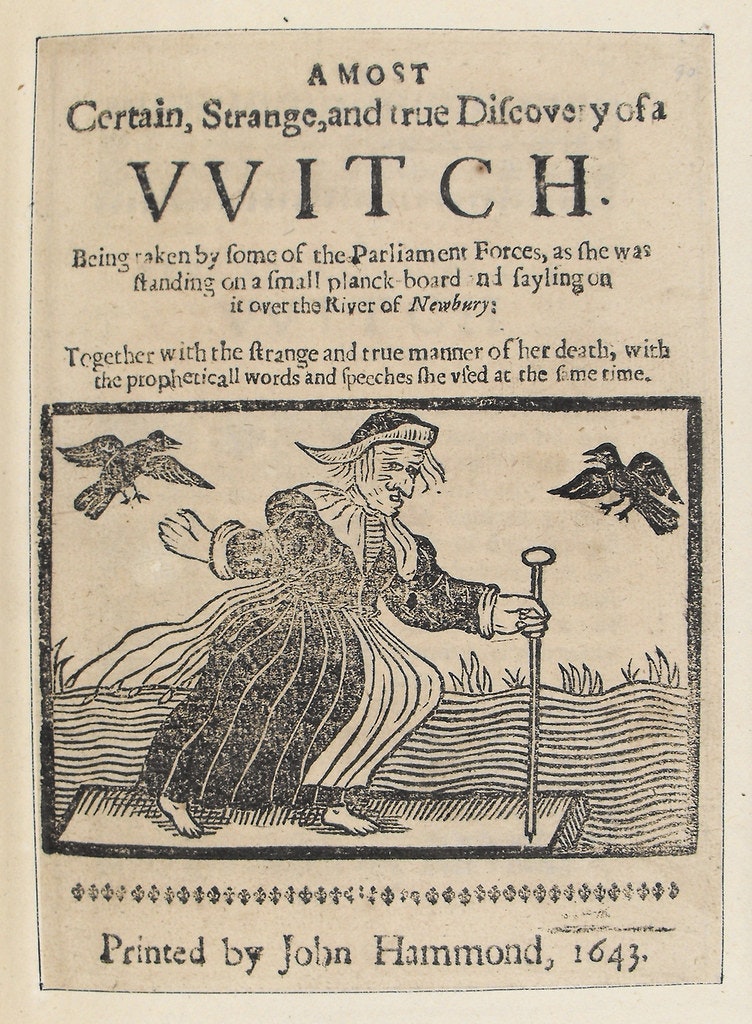

Witches in New Amsterdam?

by Wilfred B. Talman

de Halve Maen, October 1946

The average person who lived in Europe in the Middle Ages knew but little, and all he did know came from the lips of others who knew as little as he. Even those who could read and write were steeped in superstition.

Those who knew no better said that the stormwind was the rushing of a troop of dead men’s souls or the howling of wolflike monsters. As it beat against the boarded window and rattled the latches, cowering peasants believed that dead men possessed of diabolical living spirits sought to enter and prey upon them.

It would be good to say that our ancestors didn’t believe all this. It is interesting to say they did. Generalities are dangerous, however. Some of our ancestors did and some didn’t. Probably all were superstitious to some degree.

With the passing years knowledge grew, but certain superstitions remained. Werewolves and vampires were still creatures to be guarded against, especially at night. Night air was “harmful” and was excluded by carefully locked windows. To make doubly sure, householders built their bed into the wall and put doors on them. Warmth and safety were thus assured.

We know that our ancestors who came from the Netherlands were fond of gathering before the open fireplace in the evening and telling ghost stories, or “sprookjes” as the children called them. Then they crawled into their bunks and closed the doors after them. Pioneers in Ulster County — and Ulster was probably no exception — found still more utility in these closeted “slaapbanks.” They took their newly-made cheeses to bed with them, it is said, and let the heat of their bodies ripen the fragrant kaas.

Contact with the Indians and with the legends of their own slaves may have revived some of the superstitious beliefs of the colonial Dutch. The red men believed in witchcraft and their medicine men had much knowledge of the worldwide werewolf legends. At times the Hudson River was referred to as Muheakkanuck, “the wolf with magical powers” and on its east bank was Pocanteco, “the dark forest,” which the Indian thought was peopled with evil spirits.

Jesuit missionaries visiting Nieuw Amsterdam told of the hideous “loup-garou” as the werewolf was known in France. Exposed as they were to heathen belief and saturated with handed-down ghost-lores from the Continent and the many-sided superstitions of the sea in which their forefathers had believed, it is little wonder that before long the Dutch settlers peopled the Hudson highlands with mythical beings.

There was Dwerg, lord of Dunderberg, in honor of whom every Dutch skipper had to furl his topsails lest a tremendous gust of wind heeled over his ship in imminent danger of capsizing. Besides the darker spirits in Pocanteco, there were the witches that hung on the outskirts of every settlement and from time to time swooped down on barns and either frightened horses in their stalls or rode them to a witch’s sabbath so that they were covered with froth and panting in the morning. Knowing glances between the slaves or the growing young men of a family, who liked to race horses, sometimes led to suspicions of other nightly sports involving the horses, however. Dozens of spectral beings were conjured up in the inventive minds of slaves to frighten the master’s children into doing or not doing something.

All the elves and gnomes and bewitched persons that Washington Irving borrowed from Germanic folklore seem to have had a parallel, in spite of their supposed origin, in the Hudson Valley itself. Though Irving may have given the world the impression that the Hudson River Dutch were a blundering bunch of bumpkins, the spirits he introduced in his stories seem to be much the same as those the Dutch and Indians believed in, and therefore belong immemorially to that part of the country.

Sometimes on his own behalf and sometimes in the wake of Indian lore, the Dutchman named a dale into which the rays of the moon did not reach “the dark valley,” or placed on old maps such names as “Dunker Kil” (the dark stream), “Spook Rock,” or “Spook Hollow.”

In spite of the Dutchman’s apparent belief in the supernatural, there were no witchcraft scenes in New Netherland so violent as those in Salem, Massachusetts. True, some witches were brought to trial and acquitted in Hempstead, Long Island, in very early time, but neither the witches nor the prosecutors were Dutch. There is a story of some Dutchmen having chased a witch along Old Place Road on Teunison’s Neck in Staten Island, but they didn’t catch her.

The last trial for witchcraft in the State of New York — and here most of the accusers were Dutch — took place in 1816 scarcely half a mile from the old Clarkstown Church, near what is now West Nyack, New York. Naut Kaniff, an old Irish woman accused by her neighbors of witchcraft, was to be thrown into the pond of Pye’s fulling mill, in accordance with a custom dating far back into the Middle Ages. Squire Yaupy De Vries suggested that instead she be placed on the mill scales with the wood-and-brass-bound Dutch family Bible in the opposite pan. Naut Kaniff outweighed the Bible, and thus cleared herself of the charges.

Whatever witchcraft existed within the boundaries of New Netherland seems to have been largely of the harmless variety and essentially good, clean fun for those who believed in it and those who enjoy telling about it.