by Valerie van Kooten

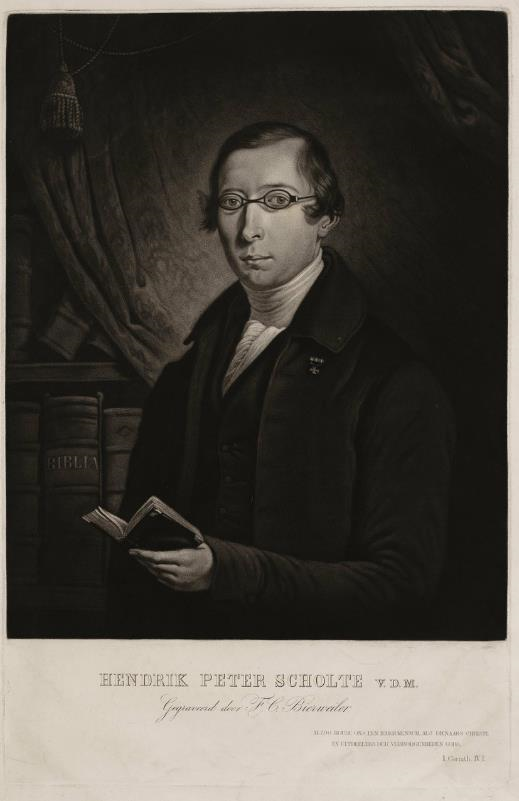

What does it mean to be of Dutch extraction in the United States? Pella, situated on the Iowa plains, was the destination of choice for hundreds of Dutch families, led by Hendrick Pieter Scholte, after the Afscheiding (Secession) of 1834 split the Dutch Reformed Church. What is still Dutch and what has changed over time? Valerie Van Kooten, Executive Director of the Pella Historical Society and Museums, tells us about her childhood.

My name is Valerie Terpstra Van Kooten. I was born in Pella, Iowa, and raised on a farm two miles west of Pella. I knew from the earliest days that the abstract to our farm documented that the land was originally transferred from Hendrik Peter Scholte to Jacob De Haan and Cornelis Welle, dividing it into two farms, with my family purchasing the De Haan half in 1971. Later, I was to find out that almost everyone’s abstract in Pella showed Scholte as the original land holder. We weren’t unique in that.

Letter of Secretary Janssen to Rev. C.W. Pape at Heusden, regarding Hendrik Scholte, 22 May 1834. Written at the time of the Secession, the letter refers to the ecclesiastical procedures in process against Scholte. Janssen also indicates that, “now that the Ultramontanist Reformed are so turbulent,” stringent measures will have to be taken against ministers who refuse to toe the line.

National Archives of the Netherlands, coll. 2.07.01.03, Archive of the Department of Reformed and Other Worship, except Roman Catholic, 1815-1870, inv. no. 1555.

Dutch Through and Through

As far back as I can determine, my ancestors on all four sides of my family were Dutch. On my mother’s maternal side were the Hoksbergens and Van Wyks, one of whom, Willem Pieters van Wijk, signed the 1834 Secession document. When the new Haarlemmermeerpolder provided more farmland in the 1850s, the Van Wyks first moved from Brabant to North Holland, and then emigrated to America in the 1880s. On my mother’s paternal side were the Beyers and the Van Zees, one of whom, Stephanus Van Zee, came with Scholte in 1847 on the Pieter Floris. The Beyers had long made their home in Veenendaal in Gelderland, where many still live.

My father’s side of the family came later. On his mother’s side, the Wouterses and the Van Oenens from Amersfoort came in 1909. I still remember my great-grandma Sientje Van Oenen, a petite woman who caught rainwater outside her window to wash her face. She had come to Iowa when she was twenty, alone. My father’s paternal side had a more interesting history. The Terpstras left Sint-Anna Parochie, Friesland, in 1892, ending up in Paterson, New Jersey, where they stayed for several years before moving to Iowa. The Vande Voorts left Dodewaard, Gelderland, in 1911, the parents and seven children, one of whom was my great-grandmother Marie Vande Voort Terpstra. She used to tell me a story about her own great-grandmother, Agatha Miering, who had been the daughter of a duke and who had been disinherited by her family for marrying one of the estate’s gamekeepers, a young mijnheer Vande Voort. I wondered for years whether this romantic love story was true and discovered, years later, that, by and large, it was. My husband’s family has a similar path—Arkemas, Van Kootens, Schuts, Bruxvoorts….all Dutch. You can imagine how surprised I was to send in my DNA sample to ancestry.com and found I was 21% Scandinavian. I guess it’s that Frisian Viking blood!

My father’s side of the family came later. On his mother’s side, the Wouterses and the Van Oenens from Amersfoort came in 1909. I still remember my great-grandma Sientje Van Oenen, a petite woman who caught rainwater outside her window to wash her face. She had come to Iowa when she was twenty, alone. My father’s paternal side had a more interesting history. The Terpstras left Sint-Anna Parochie, Friesland, in 1892, ending up in Paterson, New Jersey, where they stayed for several years before moving to Iowa. The Vande Voorts left Dodewaard, Gelderland, in 1911, the parents and seven children, one of whom was my great-grandmother Marie Vande Voort Terpstra. She used to tell me a story about her own great-grandmother, Agatha Miering, who had been the daughter of a duke and who had been disinherited by her family for marrying one of the estate’s gamekeepers, a young mijnheer Vande Voort. I wondered for years whether this romantic love story was true and discovered, years later, that, by and large, it was. My husband’s family has a similar path—Arkemas, Van Kootens, Schuts, Bruxvoorts….all Dutch. You can imagine how surprised I was to send in my DNA sample to ancestry.com and found I was 21% Scandinavian. I guess it’s that Frisian Viking blood!

The fact is, many people in Pella can trace their Dutch roots back generations. And it shocked me, when I started college, that my classmates couldn’t go back more than two to three generations. They’d say, “Well, I’m a mutt,” or “I’m about ten nationalities all put together.” That was unfathomable to me. All of my childhood friends were Dutch, with last names of Rozenboom, De Zwarte, Huisman, and Langstraat. Any one of them could recite a genealogy without thinking twice. We were Dutch through and through and proud of it.

And, of course, we had Tulip Time. For three days in the beginning of May, we donned very inauthentic Dutch costumes and marched with our classmates in the parades. The costumes were incredibly generic, not from any province really, and more resembling Little House on the Prairie costumes. If it were unusually cold, our mothers would pin a lacy baby blanket around our shoulders and close it with a brooch. If being in Tulip Time wasn’t Dutch, what was?

Reformed and Christian Reformed

The one thing that did divide the Dutch into two camps in Pella was their church affiliation—there were those who belonged to the Reformed Church and mostly attended public schools. I didn’t know most of those kids, unless they happened to play softball on my city league team or attended my 4-H club. The Christian Reformed kids went to the Christian schools and ran in their own circles. Until I was in high school, I sincerely thought a “mixed marriage” was one where a Christian Reformed girl married a Reformed boy, or vice versa. Parents were very clear about this—if you marry outside your own denomination you’ll fight about where your kids go to school later. And to be honest, that was true. I saw several of my friends’ marriages battle it out on school choice. Maybe my mother was right on this. There were a few kids who mixed the two systems—maybe attended the Christian Reformed Church but went to public school or went to Christian School and the Reformed Church. My father was one of these and said he never felt as if he belonged in either camp. He swore he would never do that to his children.

Students at Pella Christian were often called “Offies,” a derogatory term that we weren’t sure what the origin of was. Years later I discovered it came from Afscheiding. So “offies” were separated, different. The ironic part of this was that anyone who came to Pella was part of the Afscheiding, not just the Christian Reformed folks. The term applied to us all. As the member of a particularly conservative Christian Reformed congregation in Pella, I was thoroughly catechized. Every Sunday morning after the service—and when I got older, on Wednesday nights—my peers and I lined up in rows of chairs in a small Sunday School room to be taught by elders in our congregation, men who were, six days a week, farmers and shopkeepers and teachers. They didn’t want to be in front of a group of fifteen 4th graders, I’m sure. And their teaching was largely uninspired, more of a regurgitation of answers back to the Heidelberg Catechism questions. You wanted to sit in the middle of the row, as the teacher started at the edge and asked the question, and the student answered, or tried to. Then he repeated the question to the second student. By the time he got to you, you had heard it answered several times. Rarely was this pattern changed. Even though the way we were taught the catechism was by rote—mechanical and stiff—I still treasure some of the questions and answers fifty years later. And I still believe those men did their best.

When I reflect on my growing-up years, I’m not sure what’s particularly Dutch, what’s particularly living on an Iowa farm, and what’s particularly American. Being on a farm meant we ate breakfast, dinner, and supper, not breakfast, lunch and dinner. Being Dutch meant we ate things like rice and raisins and “melk” pop and “oliebollen”, Being an American meant we celebrated July 4 and pledged allegiance to the flag. But often our lives were a unique hybrid that incorporated all of these things.

Tulip Time Parade float

This float is about the story of a reluctant pioneer: Maria Hendrika Elisabeth Scholte, the wife of Hendrik Scholte. Maria did not want to go to the New World and leave her family, the grave of her first baby and her beautiful house in the Netherlands. After arriving in Pella she and her husband first lived in a log cabin in what is now Central Park in Pella. The main thing that Maria was looking forward to was the arrival of her collection of Delftware, which was still to be delivered. When it finally arrived, Maria and her maid Dirkje eagerly opened the crates, only to find that very little of her Delftware had survived the journey. Only five plates, it is believed, remained unbroken. Maria was crushed. When the Scholte House, built just across from the log cabin, was finished, Maria made a path of broken Delftware from the doorway of the cabin to the door of her new home. Decades later, Highway 163 (Washington Street) was constructed between two houses and pieces of Delftware were found. Some are now on display in Maria’s Tea Room, on the west side of the Scholte House, the main building of the Pella Historical Society. Hence this float with a crate labeled “Breekbaar,” fragile.

Photo by Andrew Schneider, KNIA/KRLS Radio.

The competition between the public and private school systems is not as intense, I don’t believe. Both are excellent schools; each has its good and bad qualities. Kids get to know their counterparts from the other school much earlier than we ever did, and that’s a good thing. Pella Christian’s marching band wear red wooden shoes; Pella Community’s athletes and students are known as “The Dutch.” You see more intermixing of Christian school kids in Reformed churches or the other way around. The stigmas are disappearing.

And Pella has exploded with non-Dutch, as our largest industries—Pella Corporation, Vermeer Corporation, Lely, PPI, Central College, the Pella Community Hospital—expand. We have a large number of Laotian, Vietnamese, and Indian citizens. We’ve dropped the bumper sticker, “If you ain’t Dutch, you ain’t much.” We are slowly becoming a more inclusive, welcoming city, but we have a ways to go. Maybe we do live inside a bubble in Pella, as we are sometimes accused of doing. Maybe we do value things that have fallen by the wayside in many other towns. But my view, from inside the bubble, is pretty good.