by Jeroen Dewulf

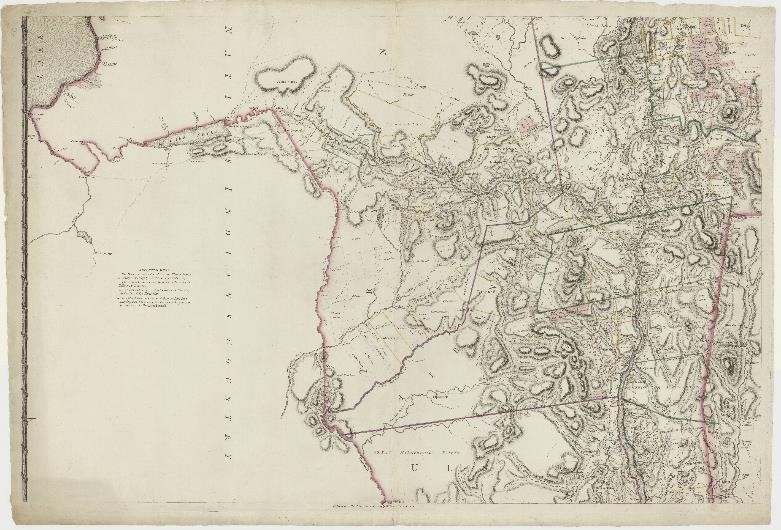

On 31 March 1817 the New York legislature decided that enslavement within its borders had to come to an end. Final emancipation would occur on 4 July 1827. Coincidentally, the date of choice was almost exactly two centuries after the Dutch West India Company’s yacht Bruynvisch arrived at Manhattan on 29 August 1627. The ship transported the first group of enslaved Africans to New Amsterdam and thus introduced the institution of enslavement into what is now New York State. Among the first arrivals was Mayken van Angola, whose life was the topic of an earlier blog in this series. One of the enslaved women emancipated two hundred years later was Isabella Van Wagenen, better known under the name she choose for herself: Sojourner Truth.

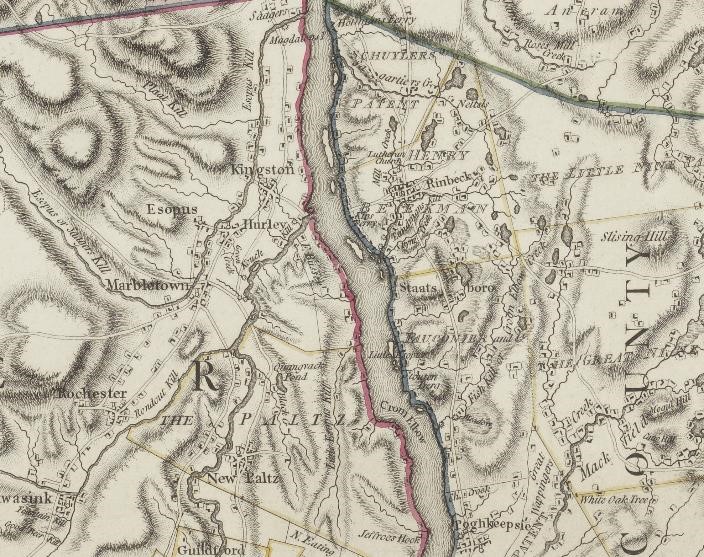

It is little known that Sojourner Truth (c. 1797-1883), one of the icons of America’s Black liberation movement, was a native speaker of Dutch. In her famous Narrative (1850), she identified herself as “the daughter of James and Betsey, slaves of one Colonel Ardinburgh, Hurley, Ulster County, New York,” who “belonged to that class of people called Low Dutch.” The latter refers to descendants of seventeenth-century inhabitants of New Netherland, who remained in America after the English takeover in 1664. Many of them held on to their Dutch identity for several generations. This was, in particular, the case in the New York Hudson Valley, where Peter Kalm, a Swedish traveler, observed in 1749 that almost all people “speak Dutch, have Dutch preachers, and divine service is performed in that language; their manners are likewise quite Dutch.”

With Hardenbergh in Hurley

The family’s Christian zeal did not imply opposition to slavery. The 1790 census of the town of Hurley lists Johannes Hardenbergh as the owner of seven enslaved people, which made him one of the largest slaveholders in the region. Among them were the parents of Sojourner Truth, then still called Belle, short for Isabella, who, born circa 1797, grew up in an entirely Dutch-speaking environment. Significantly, when she was sold at the age of nine to the English-speaking Nealy family, Isabella had tremendous difficulties understanding her new owners. In her Narrative, she complained that “if they sent me for a frying pan, not knowing what they meant, perhaps I carried them the pot-hooks and trammels.” Apparently, she did not learn much English during the short time she spent with the Nealies, because the daughter of John Dumont, the slaveholder who bought her around 1810, recalled that upon arrival “she could neither talk nor understand anything but low or Holland Dutch.” Although she later became fluent in English, Truth is known to have kept a strong Dutch accent all her life and when she later recalled her mother’s reaction to the news that her daughter would be sold, she accidentally slipped back into her mother tongue: “My poor mother would weep and say: ‘Oh! Mein Got, mein Got, my children will be sold into slavery!’”

Truth’s case was not exceptional. Graham Hodges and Alan Brown’s anthology of runaway advertisements from New York and New Jersey, dating from 1716 until 1783, includes 186 references to Black fugitives who spoke English, while 58 of them spoke Dutch. Although those who spoke Dutch were mostly bilingual, several of them had, like Isabella, difficulties making themselves understood in English. A man called Cyrus, for instance, only spoke “Dutch and very bad English,” while a certain Adonia spoke “pretty good Low Dutch” but “little English.”

Low Dutch

Some African Americans preserved an emotional attachment to the Dutch language after abolition. When interviewed in the early twentieth century, an elderly Black person with roots in the Hudson Valley recalled that his ancestors, “were Dutch and proud of it” and that his “Aunt Sebania” told him “about her great-grandmother, a stern old lady who spoke and understood English, but who refused to speak it except in the privacy of her home. In public she spoke Dutch, as any proper person should do, a dignified language.” Such statements should be treated with caution, since they could transmit the false impression that slavery among the Dutch was a benign system. It is not difficult to find examples of racism and cruel punishments in Dutch-American circles. In August 1885, for instance, the Troy Daily Times quoted from an eighteenth-century report about the heavily Dutch Bergen County, where “two slaves were subjected to 500 lashes each … for an assault upon a man” until “one of the slaves died.” The report also referred to a bill “for wood carted for burning two Negroes” and mentioned that, by the late nineteenth century, older people in the region still remembered “the burning of two Negroes at the other side of the Hackensack.”

Dutch-American farmers were among the fiercest opponents of John Jay’s Gradual Emancipation Law that would free all enslaved children born after July 4, 1799, and accused the New York governor of wanting “to rob every Dutchman of the property … most dear to his heart, his slaves.” Delaware County politician Erastus Root recalled, with reference to this debate, that “the slaveholders at that time were chiefly Dutch. They raved and swore dunder and blitzen that we were robbing them of their property.”

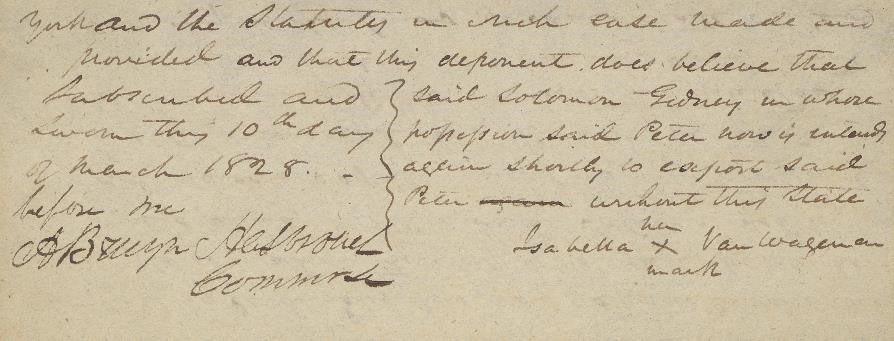

Once it became clear that abolition was inevitable, some Dutch-American slaveholders attempted to talk their enslaved workers into deals that kept them in bondage for as long as possible. Dumont, for instance, promised Isabella her freedom if she agreed to work for one more year. At the year’s end, however, he broke his word. Isabella reacted by fleeing the house with her youngest daughter. She found rescue with another Dutch-American family, the Van Wagenens, where she stayed until emancipation on July 4, 1827. Meanwhile, she took Dumont to court for having sold her son Peter to a slaveholder in Alabama, which violated the law. Isabella won the case and was reunited with Peter.

Once it became clear that abolition was inevitable, some Dutch-American slaveholders attempted to talk their enslaved workers into deals that kept them in bondage for as long as possible. Dumont, for instance, promised Isabella her freedom if she agreed to work for one more year. At the year’s end, however, he broke his word. Isabella reacted by fleeing the house with her youngest daughter. She found rescue with another Dutch-American family, the Van Wagenens, where she stayed until emancipation on July 4, 1827. Meanwhile, she took Dumont to court for having sold her son Peter to a slaveholder in Alabama, which violated the law. Isabella won the case and was reunited with Peter.

Civil War

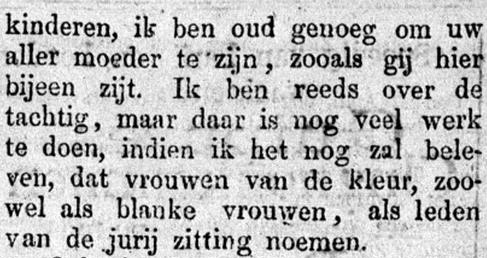

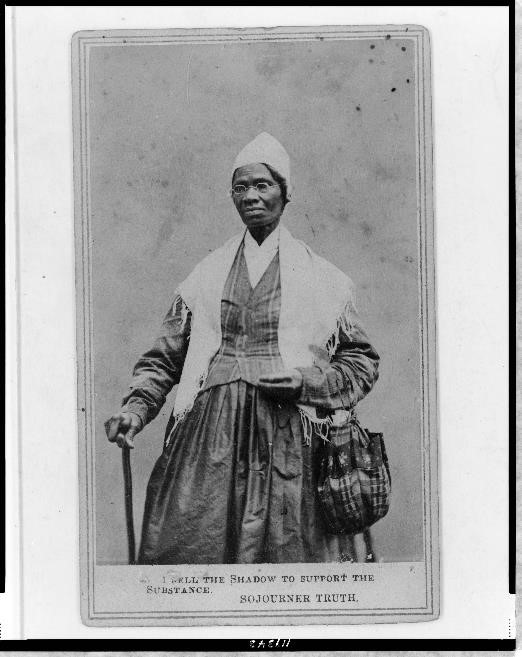

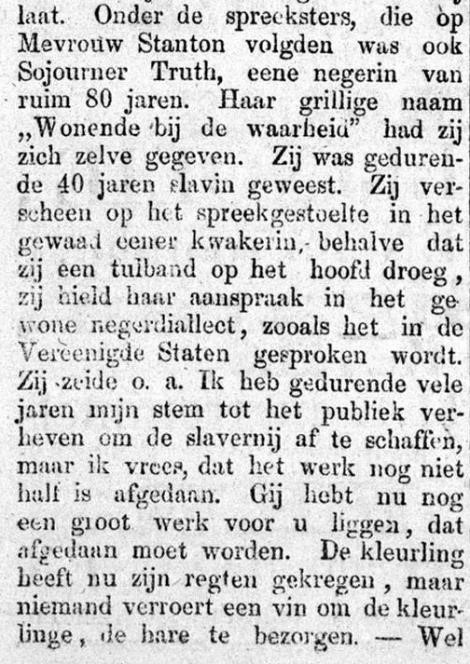

During the Civil War, Truth became politically active by assisting at the recruitment of Black troops for the Union Army. In that capacity, she had an audience with President Lincoln in 1864. During her time in Washington, D.C., Truth challenged the de facto segregation in the city’s transportation system by insisting on her right to take a seat on streetcars. With her decision to use civil disobedience as a strategy to challenge segregation in public transportation, Truth anticipated Rosa Parks by almost a century. However, Truth could also be an uncomfortable voice within her own community. For instance, when Douglass defended the use of violence in the fight for racial justice at a meeting in 1852, she interrupted him with the words “Frederick, is God gone?” and, in 1867, she provocatively stated that “if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs … the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before.”

During the Civil War, Truth became politically active by assisting at the recruitment of Black troops for the Union Army. In that capacity, she had an audience with President Lincoln in 1864. During her time in Washington, D.C., Truth challenged the de facto segregation in the city’s transportation system by insisting on her right to take a seat on streetcars. With her decision to use civil disobedience as a strategy to challenge segregation in public transportation, Truth anticipated Rosa Parks by almost a century. However, Truth could also be an uncomfortable voice within her own community. For instance, when Douglass defended the use of violence in the fight for racial justice at a meeting in 1852, she interrupted him with the words “Frederick, is God gone?” and, in 1867, she provocatively stated that “if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs … the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before.”

By the end of her life, Truth moved to Battle Creek, Michigan, where she passed away in 1883. While largely forgotten afterwards, her legacy was rediscovered in the context of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1972, Shirley Chisholm referred to Truth as a model when she, as the first Black woman in history, announced her candidacy for the presidential elections, while bell hooks chose the words “Ain’t I a Woman?” as the title for her famous 1981 book on Black women and feminism. Born as an enslaved female who struggled to speak English and never acquired literacy, Truth acquired nation-wide fame in 2009 when, in the presence of First Lady Michelle Obama, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, and Senator Hillary Clinton, she became the first African-American woman to be honored with a bust in the U.S. Capitol building.

A crucial decision in Truth’s life was her move to Florence, Massachusetts, where she joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in 1844. This utopian communitarian society that united people of all colors and social backgrounds brought her in touch with some of the nation’s leading abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. The latter financed, in 1850, the publication of the life story that the illiterate Truth dictated to the Anglo-Saxon Olive Gilbert. Unfamiliar with Dutch culture, Gilbert’s transcription of Truth’s Narrative is full of misunderstandings. An example is Truth’s reference to her mother as “mama Bet,” which Gilbert transcribed as “Mau-Mau Bett.” Ever since, virtually all studies on Truth assume that her mother had the mysterious, African-sounding name Mau-Mau.

A crucial decision in Truth’s life was her move to Florence, Massachusetts, where she joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in 1844. This utopian communitarian society that united people of all colors and social backgrounds brought her in touch with some of the nation’s leading abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. The latter financed, in 1850, the publication of the life story that the illiterate Truth dictated to the Anglo-Saxon Olive Gilbert. Unfamiliar with Dutch culture, Gilbert’s transcription of Truth’s Narrative is full of misunderstandings. An example is Truth’s reference to her mother as “mama Bet,” which Gilbert transcribed as “Mau-Mau Bett.” Ever since, virtually all studies on Truth assume that her mother had the mysterious, African-sounding name Mau-Mau.