written by Bas Blokker

Travelling from Washington D.C. to Milwaukee, Dutch journalist Bas Blokker makes a stop-over in Hurley, N.Y., and discovers its Dutch history. His curiousity is piqued and he dives into the past to find the nineteenth-century views of the Dutch colonizers very different from modern ones.

During the last five years, I always crossed the Susquehanna River just north of Baltimore when driving from my house in Washington D.C. to New York. Once on the bridge the same scene unfolded again and again in my mind’s eye: a sailing ship changing course from the Chesapeake Bay to enter the river’s mouth and drop anchor at what is now Havre de Grace or Garret Island. The seventeenth-century immigrants, dizzy from the journey, began to disembark. What would have been the new European arrivals’ first impressions? The richness of resources? The unfamiliar animals? The ‘wild’ people? Sweet water could be found everywhere, they would even name a river after it, the Fresh River. Trees abounded as far as the eye could see, so plenty of timber and fruits were available. Fowl and game was in abundance and there was not a lord or master in sight to impose hunting rights. “The gorgeous hues of the maples and of the ‘American calico plant’, and the splendor of the scenery,” as William Elliott Griffis would put it in The Story of New Netherland. “Whatever we desire in the paradise of Holland, is here to be found,” according to a seventeenth-century colonist quoted by Russell Shorto in The Island at the Center of the World. Did it indeed appear as the promised land to them, I wonder? By the time I was about to be swallowed up completely by the past, the horn of a passing car pulled me back to the present. Interstate 95 is one of the busiest routes in the U.S.

Stopover in Hurley

In August 2020, during the first summer of the pandemic, my wife Jutta and I drove north for a few weeks’ break. Our subsequent destination was the Democratic National Convention in Milwaukee, scheduled to start on August 17, which was eventually turned into a virtual event. We had booked a room in the Stone House Bed & Breakfast in Hurley, Ulster County, N.Y., as our first stop on the way. Upon arrival the owner informed us it was the oldest house in the area, built between 1705 and 1720 by Cornelis Kool, a descendant of the early Dutch immigrants. All the rooms were named after the paintings of Johannes Vermeer, except for the ‘Groote Kamer’, the largest room. Our room was The Lacemaker, furnished with a four-poster on a wide-board floor, a simple wooden table, and two chairs. New York State pandemic regulations obliged us, as out-of-state visitors, to remain at the Stone House for at least ten days. But with a smile the proprietor put the required form in a drawer, where it was likely to stay for a very long time.

Had we deliberately picked a place with some Dutch history? No, it was pure coincidence. To be blunt, the historical perspective of a foreign correspondent of a Dutch newspaper in the U.S. rarely reaches back beyond the twentieth century, with the occasional exception of the Civil War. A rare exception occurred on August 14, 2019, the day that the issue of the New York Times Magazine on the first sale of enslaved people in North America hit my porch. It alerted me to 1619 as an important year in American history. I became aware of another date later: August 29, 1627, when the Amsterdam ship Bruynvisch brought the first enslaved Africans to Manhattan.

My musings at the mouth of the Susquehanna River were not founded on historical insights. Instead, they were but a figment of my imagination. The natural beauty of America did confront me with the past on a regular basis. In Hurley that experience took on a Dutch shape: Holland in the age once called golden. My knowledge of the Dutch colonists in the first decades of the seventeenth century was limited to what I read in The Island at the Centre of the World. The next morning we enjoyed breakfast in room with a low ceiling and sash windows. When I dropped Shorto’s name, the owner showed me a framed article hanging in the hallway: Russell Shorto had visited the Stone House in the previous year and had published an article on his ‘Drive Back in Time’ through the Hudson Valley in The New York Times.

Stone Houses

Due to the pandemic the small museum in Hurley remained closed during the summer of 2020. But in Hurley you did not need a museum to encounter Dutch history. At the Hurley Library on Main Street we found a sign with a map showing the way to the houses of Dutch families. In 1661 a number of Dutchmen from nearby Wiltwijck (modern-day Kingston), sought out good arable land near the Esopus Creek. Within a year they built a ‘Nieuw Dorp’ (New Town)—many of the names of places in the Hudson are simply references to towns in the Netherlands, preceded by ‘new’. One of the new land owners along the Esopus Creek was the director general of New Netherland himself, Petrus Stuyvesant.

The twelve families of the first generation of settlers built timber houses, none of which are still extant. The ‘Dutch’ houses currently standing are eighteenth-century stone buildings—some very early-eighteenth—built when the new village had been renamed Hurley. At the junction where Main Street becomes Zandhoek Road a 1720s house stands, about eighteen feet in length, with sash windows and a slate roof, which looks remarkably similar to houses in Jutphaas or Dordrecht. Tradition, as an historical marker informs passers-by, has it that this was the site of a small party in honor of George Washington, commander of the Continental Army, travelling from West Point to Kingston in 1782. But that may not be the full story. Purportedly, a delegation of villagers escorted the General and stopped at Colonel Wynkoop’s house. The Colonel honored the General with a long speech in Dutch, which the villagers could understand, but Washington did not. All the time, Wynkoop remained at the threshold of his home, nice and dry with a warm fire at his back, while the general sat on horseback out in the rain.

The old cemetery of Hurley, situated on a hill overlooking the Esopus Creek, is awash with Dutch names, often anglicized: Cool, Cole, Wynkoop, Van Keuren, De Witt. The deep respect with which the Americans honor their dead often struck us. In the Netherlands graves are frequently cleared, whereas in the U.S. you can find many burial grounds in the U.S. with very old graves. The common American negligence of old buildings does not extend to the last resting places of ancestors.

Old maps

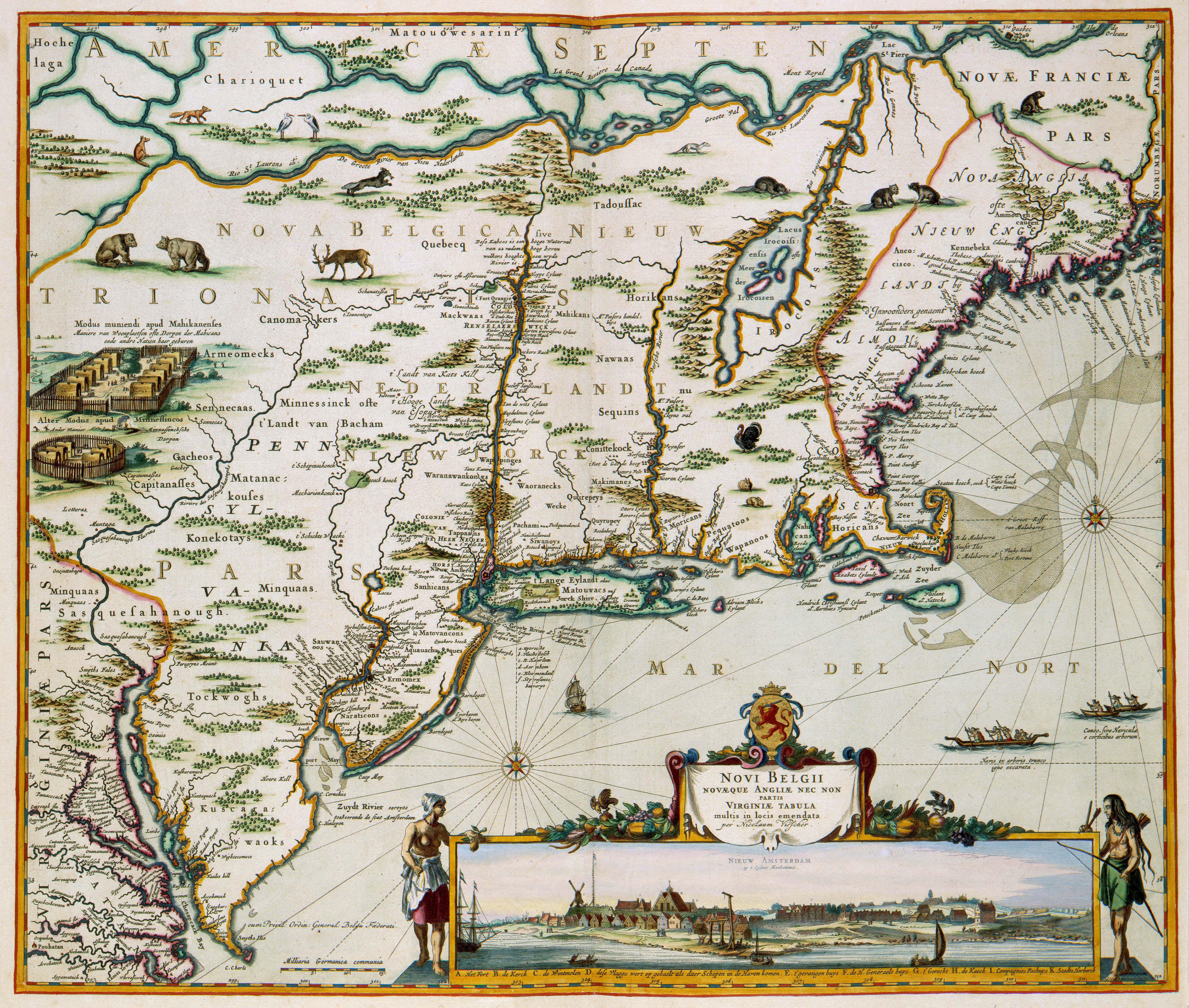

Back in Washington I looked up maps of the mid-Hudson Valley in the seventeenth century. On a 1684 map by Nicolaes Visscher, entitled Novi Belgii Novaque Angliae Tabula, I found the name ‘Horley’, with ‘alias Nieustuk’ added to it, next to ‘Wiltwijck’, near the winding line that indicated the ‘Groote Esopus rivier’. An earlier edition of the map, dating from 1656, does not show the two villages yet. Thus the speed with which colonization proceeded is captured on the two versions. Visscher did not omit the original owners of the land. His maps provide their names: Minquaas, Mahikans, Horikans, Sennecaas, Minnesinck.

I also read The Story of New Netherland by William Elliot Griffis, a loving description of the Dutch colonization of the Hudson Valley. Perhaps ‘loving’ is an understatement for this paean of the Dutch heritage. The tolerant and “enterprising Dutchmen” and their leaders wanted to live peacefully and honestly with the indigenous peoples on a “continent that was big enough for both its first inhabitants and the newcomers.” The institution of slavery was forced upon them by the West India Company “against the wish of the people” because “the Dutch common people were opposed to slavery.” In short, “how large are our inheritances from Dutch law, order, freedom, culture, and from those achievements for civilization and humanity in which the Netherlands so long led the world.” Later publications corrected that positive image. In Op zoek naar Nederlands New York, Jaap Jacobs points out that “Stuyvesant was the largest enslaver in New Netherland, with the exception of the West India Company.” He also considers the idea of Dutch tolerance a myth: “New Amsterdam was not as tolerant as Amsterdam.” Those not of the Reformed religion were faced with repression and in one instance a Quaker was whipped.

Esopus Wars

Griffis’ smorgasbord of admirable Dutch colonial characteristics did not include the less-than-peaceful encounters with the indigenous inhabitants. The Esopus Wars are not to be found in Griffis’ book. ‘War’ may actually be a misnomer for the incidents that occurred between 1659 and 1663. Twice the Dutch colonists engaged in deadly skirmishes with the local Esopus band, one of the subgroups of the Lenape or Lenni Lenape. They are different accounts, all of later date, of what sparked the outbreak of hostilities. In 1659 Dutch colonists attacked a group of Esopus who had gathered around a campfire to drink and became noisy. As an aside, it is remarkable how often alcohol, imported by European colonists to the ‘new’ continent, is offered as an explanation when trouble arose. After the attack in 1659, hundreds of Esopus warriors besieged the weakly defended village of Wiltwijck. The conflict ended months later, when Dutch reinforcements arrived. The Second Esopus War was both bloodier and longer. Later chroniclers of New Netherland make it out to be a premeditated ambush by the “savages.” In a speech to the New-York Historical Society on January 2, 1844, Thomas de Witt describes the attack as follows:

Griffis’ smorgasbord of admirable Dutch colonial characteristics did not include the less-than-peaceful encounters with the indigenous inhabitants. The Esopus Wars are not to be found in Griffis’ book. ‘War’ may actually be a misnomer for the incidents that occurred between 1659 and 1663. Twice the Dutch colonists engaged in deadly skirmishes with the local Esopus band, one of the subgroups of the Lenape or Lenni Lenape. They are different accounts, all of later date, of what sparked the outbreak of hostilities. In 1659 Dutch colonists attacked a group of Esopus who had gathered around a campfire to drink and became noisy. As an aside, it is remarkable how often alcohol, imported by European colonists to the ‘new’ continent, is offered as an explanation when trouble arose. After the attack in 1659, hundreds of Esopus warriors besieged the weakly defended village of Wiltwijck. The conflict ended months later, when Dutch reinforcements arrived. The Second Esopus War was both bloodier and longer. Later chroniclers of New Netherland make it out to be a premeditated ambush by the “savages.” In a speech to the New-York Historical Society on January 2, 1844, Thomas de Witt describes the attack as follows:

The Esopus Indians, (belonging to the Minisink tribe,) in the vicinity of what is now Kingston, at a time when they professed friendly relations, unexpectedly surprised the village of Esopus [De Witt’s designation for Nieuw Dorp/Hurley] under a pretence of barter, killed more than twenty, and wounded and took captive more than fifty, desolating that infant settlement.

The Esopus Wars hardly feature in The Story of New Netherland, except in veiled terms: “When the people at Esopus and on Manhattan were in terror and saw fire, blood, and devastation, those at Fort Orange found the red men ‘as quiet as lambs.’” And further on, in an error-filled paragraph, Griffis writes about the 1655 Peach War, which he seems to think took place in 1663:

A Dutchman had shot a squaw while she was stealing some peaches in his orchard, and her own tribe quickly roused to vengeance the savages of the New Jersey, Hudson River, and Connecticut regions, to the number of nearly two thousand. From sixty-two war canoes, they landed at night on the nearly defenseless Manhattan, pretending to be looking for Iroquois. After looting several houses, they were persuaded to leave the next night, but not until they had killed the squaw’s murderer and another man.

Griffis considers the ‘savages’ fully to blame for these wars. Apart from the manslaughter of a peach thief, the colonists did nothing wrong. They were friendly and interested in the “red men,” who still lived “in the Stone Age” and could be swindled out of their land, because they, as Shorto writes “had a different idea of land ownership from the Europeans.”

In contrast, Griffis is very critical about one particular Dutchman in the conflict that took place twenty years previously. In a chapter tellingly entitled “Kieft and his Indian War,” Griffis upbraides director Willem Kieft: he is rigid, rules by decree without allowing the colonists any say, and tries to impose a tax on the native people: “This was flying in the face of all Dutch precedent and principle in the Fatherland. ‘No taxation without consent’ was a maxim as old as the abolition of feudalism.” The War of Kieft was un-Dutch, Griffis opined.

Suddenly, it all seemed very familiar, this catalogue of Dutch virtues, which, if they had but been maintained, would have made the United States an even better country. Where had I read that before? I turned back to Shorto’s The Island at the Center of the World and it now struck me how its drift was determined by that nineteenth-century conception of liberal and peace-loving Dutch colonists, much superior to the English Puritans who are presented as Founding Fathers in the collective American mind. “Their form of government was a theocracy,” Shorto writes.

It was rooted in intolerance: freedom of worship, in the words of one prominent New England minister (who became president of Harvard College), was the ‘first born of all abominations.’ ‘’Tis Satan’s policy to plead for an indefinite and boundless toleration,’ declared another. The Puritans’ crackdown on alternative views was cruel, unusual, and lethal.

The Dutch were different:

They reshuffled the categories by which people had long lived, created a society with more open space, in which the rungs of the ladder were reachable by nearly everyone.

New Netherland as the birthplace of the American melting pot.

Too great an honor

Tracing the long trajectory of this New Netherland rehabilitation is fascinating. It runs from the mid-nineteenth-century historian and diplomat John Romeyn Brodhead and Thomas de Witt, officer of the New-York Historical Society, by way of Griffis to our own time. They are not promoting the Netherlands, but they mix their historical curiosity with admiration for the Dutch past. It shows in minute details: English soldiers who served in the Low Countries during the seventeenth century and return home “filled with notions of popular rights and civil liberties” (Brodhead in his History of the State New York); “Holland was, of all the powers of Europe, the most in advance of the spirit of the age, in the liberal principles of her Constitution and in the administration of it” (De Witt, speech to the New-York Historical Society in 1844); Griffis’ enterprising Dutchmen; Shorto, who is of the opinion that they carried “a tolerance of differences, the prescription for a multicultural society” across the Ocean to America.

It is too great an honor and in 2024 almost makes a Dutchman blush. And then he wonders whether it actually rings true. Let’s look at De Witt again:

Had the States-General, early after the discovery by Hudson, directed their attention to this western field, and directly extended their strong fostering influence in planting and nurturing a well-chosen colony, bearing the germ of the institutions of the fatherland—and had the valor, wisdom and patriotism of a Stuyvesant superintended it when the first forming influences were favorable, a basis would have been laid securing probably a long and prosperous continuance.

So the United States came very close to being Dutch and free instead of, well, what actually?

About the author

Bas Blokker is a journalist for NRC Handelsblad, one of the most prominent Dutch newspapers. He served as the paper’s Washington correspondent from 2018 to 2023.

About the blogseries

This is the twenty-third installment in a monthly series of blogs telling stories about the rich history shared by the American and the Dutch peoples. Authors from both countries present accounts of their own choosing, from a wide variety of perspectives, in order to give as full a picture as possible of the triumphs and heartbreaks, delights and disappointments that happened place over hundreds of years of shared history. Not all these stories are ‘feel-good history’, however. While the relations between the Dutch and the Americans have for the most part been stable and peaceful, their shared history contains darker moments as well. Acknowledging that errors have been made in the past does not diminish this friendship but, rather, deepens it.

Further Reading

- Brodhead, John Romeyn, History of the State of New York. First Period. 1609-1664 (New York, 1853).

- De Witt, Thomas, “Paper read to the Annual Meeting,” Proceedings of the New York Historical Society for the Year 1844 (New York, 1845), 51-76.

- Griffis, William Elliot, The Story of New Netherland: The Dutch in America (Boston, New York, 1909).

- Jacobs, Jaap, Op zoek naar Nederlands New York. Een historisch reisboek (Amsterdam, 2009).

- Shorto, Russell, The Island at the Center of the World: The Untold Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Founding of New York (New York: Doubleday, 2004).

Illustrations

- Main Street in Hurley. Photo Jaap Jacobs.

- The sign at Hurley Library. Photo Jaap Jacobs.

- Washington was here. Photo Jaap Jacobs.

- The old cemetery at Hurley. Photo Jaap Jacobs.

- Honoring the dead. Photo Jaap Jacobs.

- Novi Belgii Novaeque Angliae nec non partis Virginiae tabula. Nicolaes Visscher, ca. 1684. Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag. https://geheugen.delpher.nl/nl/geheugen/view?coll=ngvn&identifier=KONB01:422

- William Eliot Griffis, The Story of New Netherland: The Dutch in America. Frontispiece.